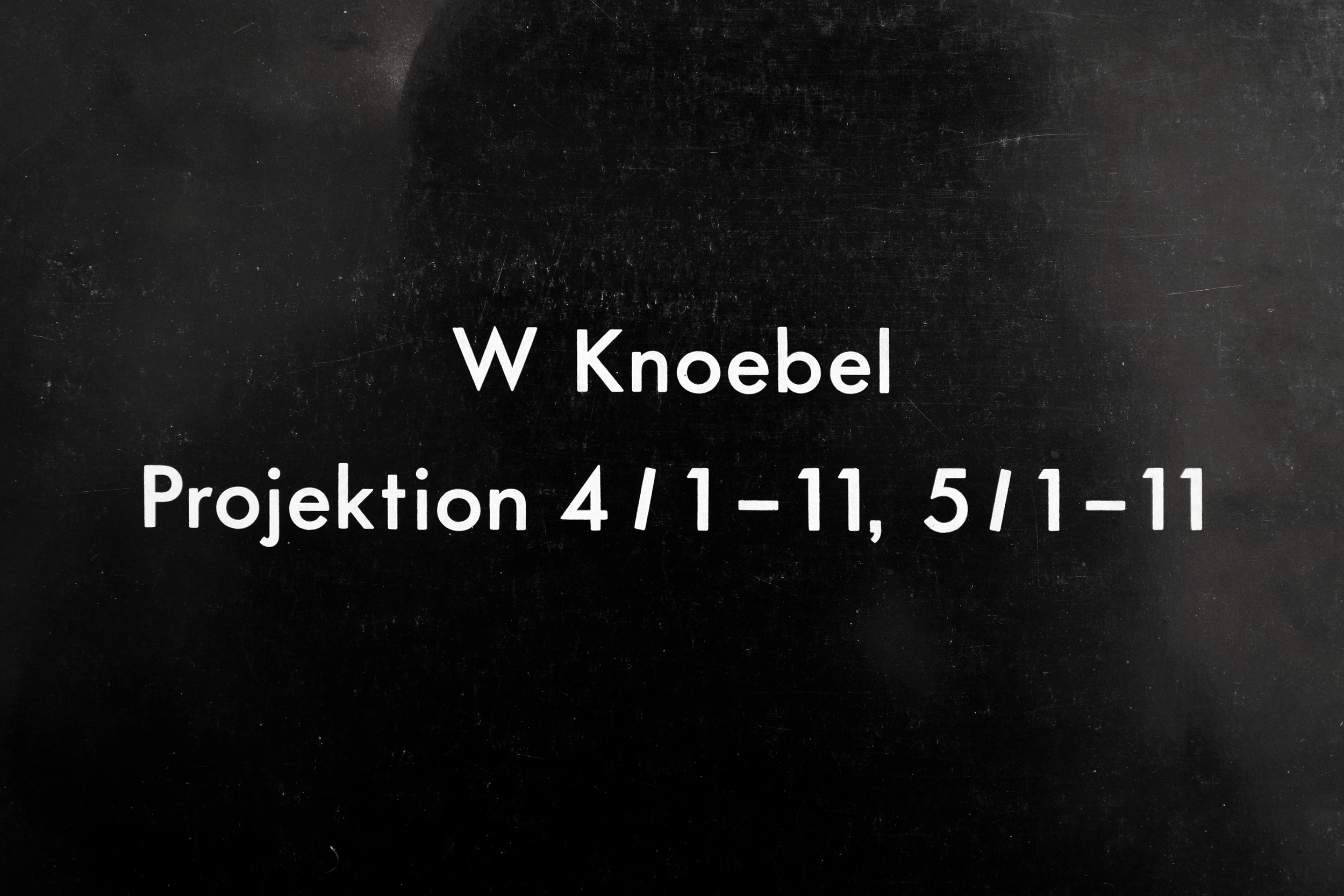

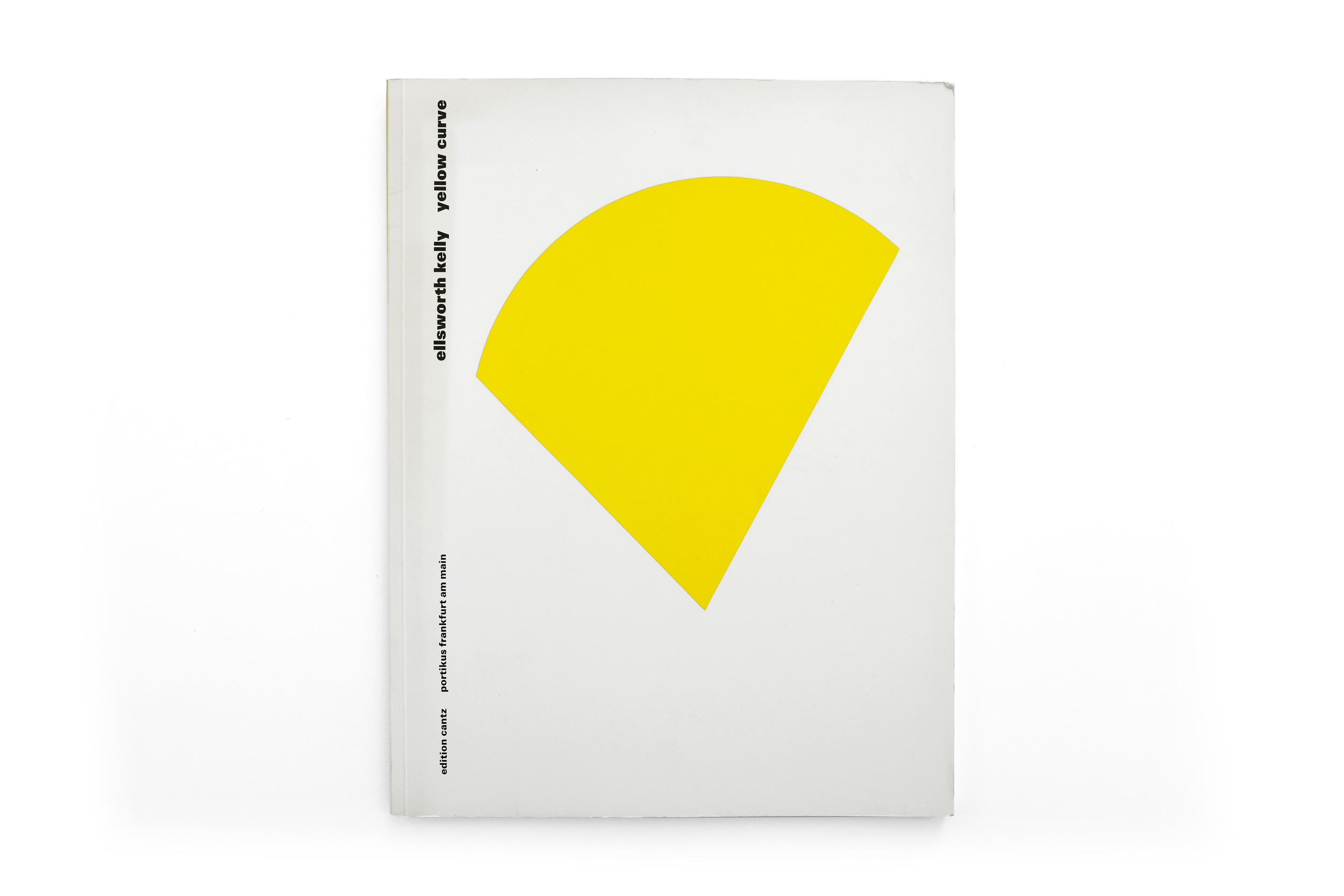

W Knoebel Projektion 4/1-11, 5/1-11

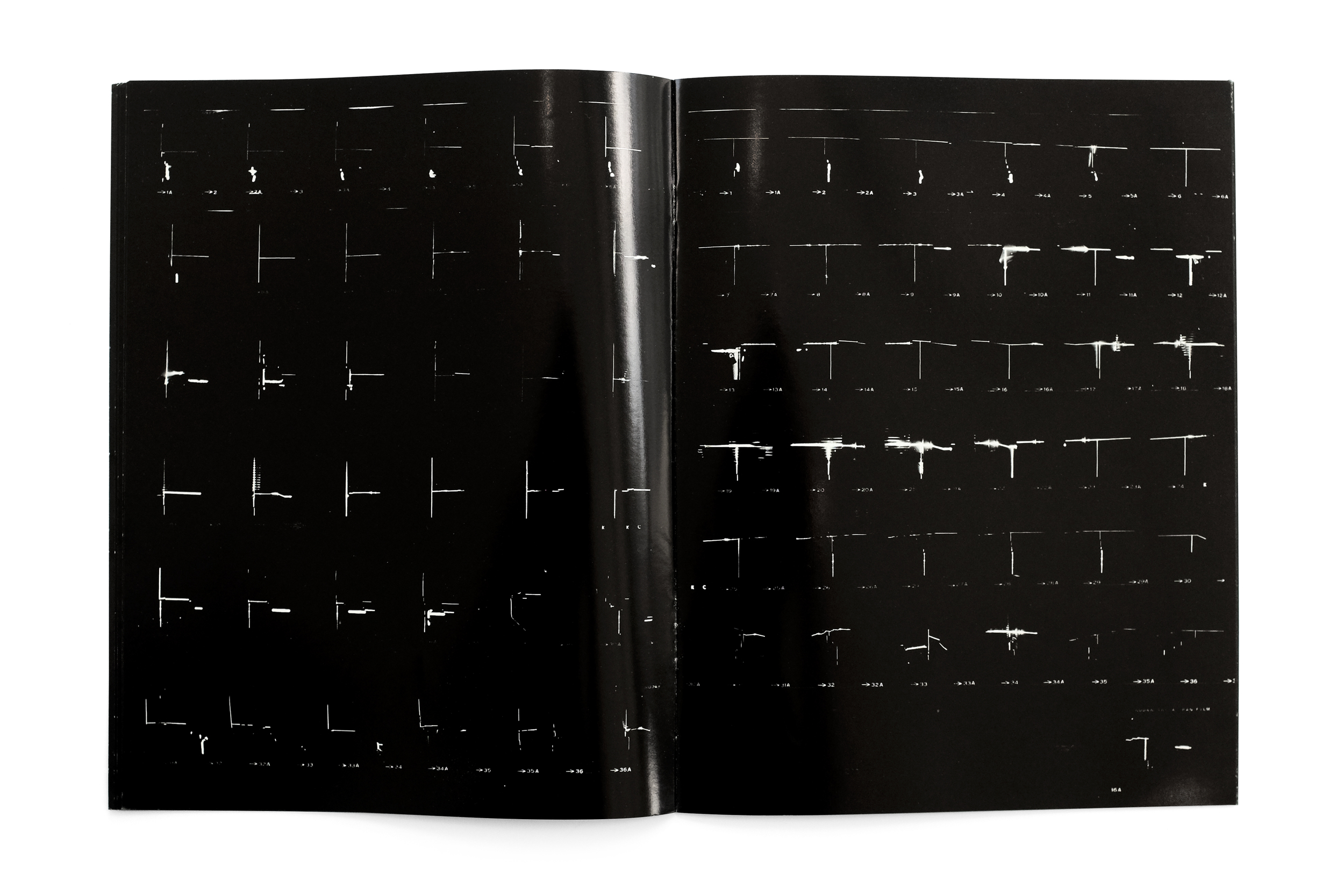

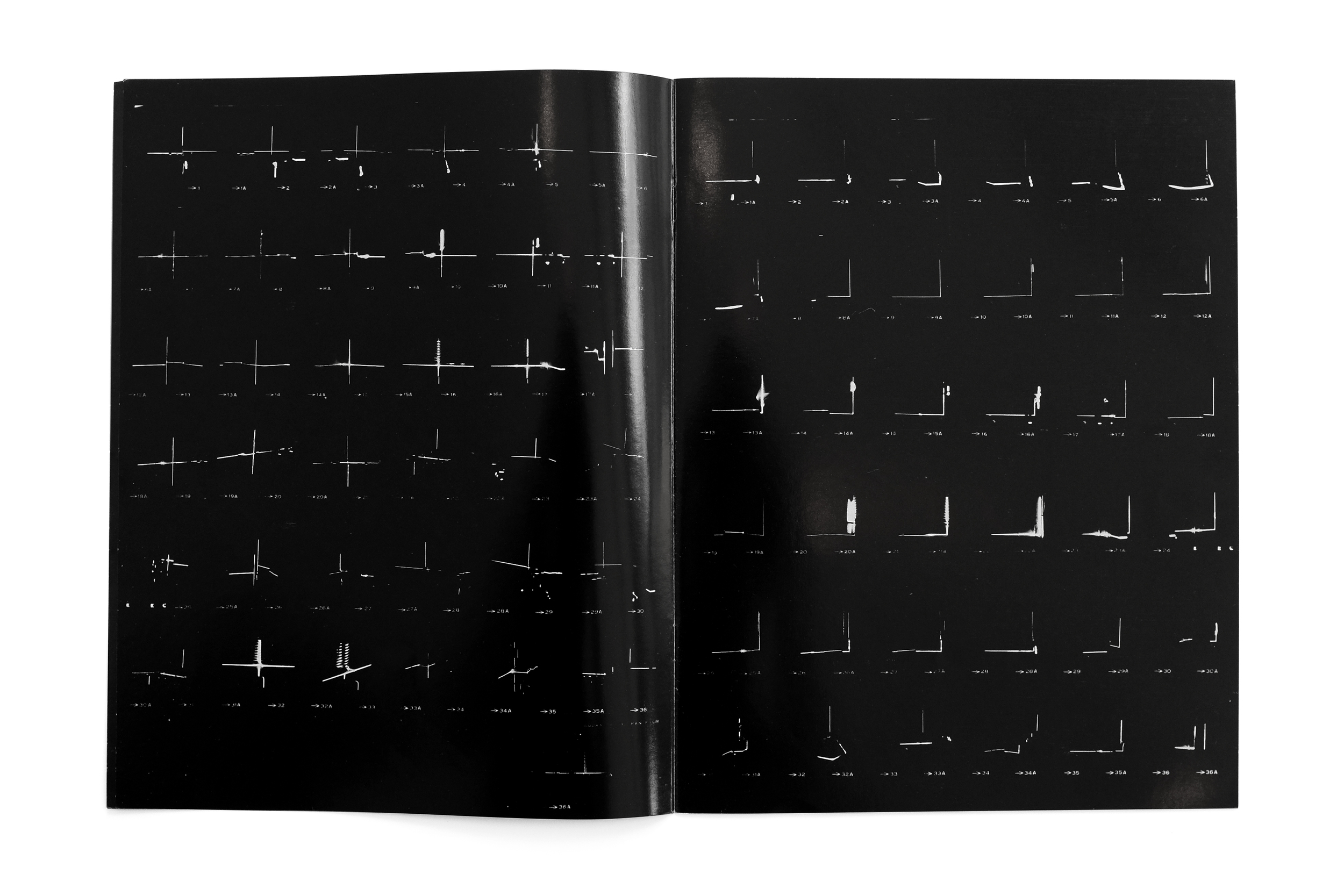

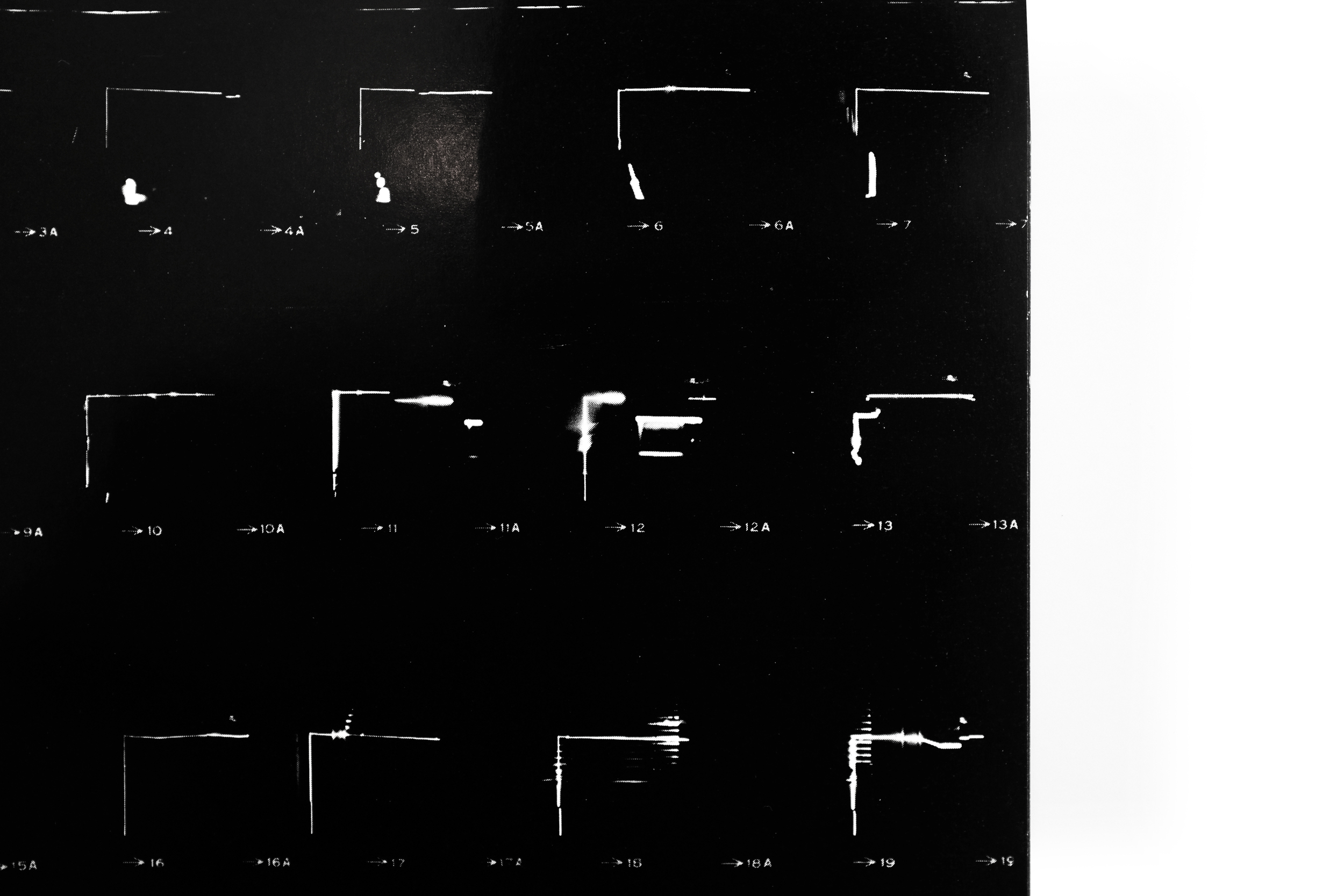

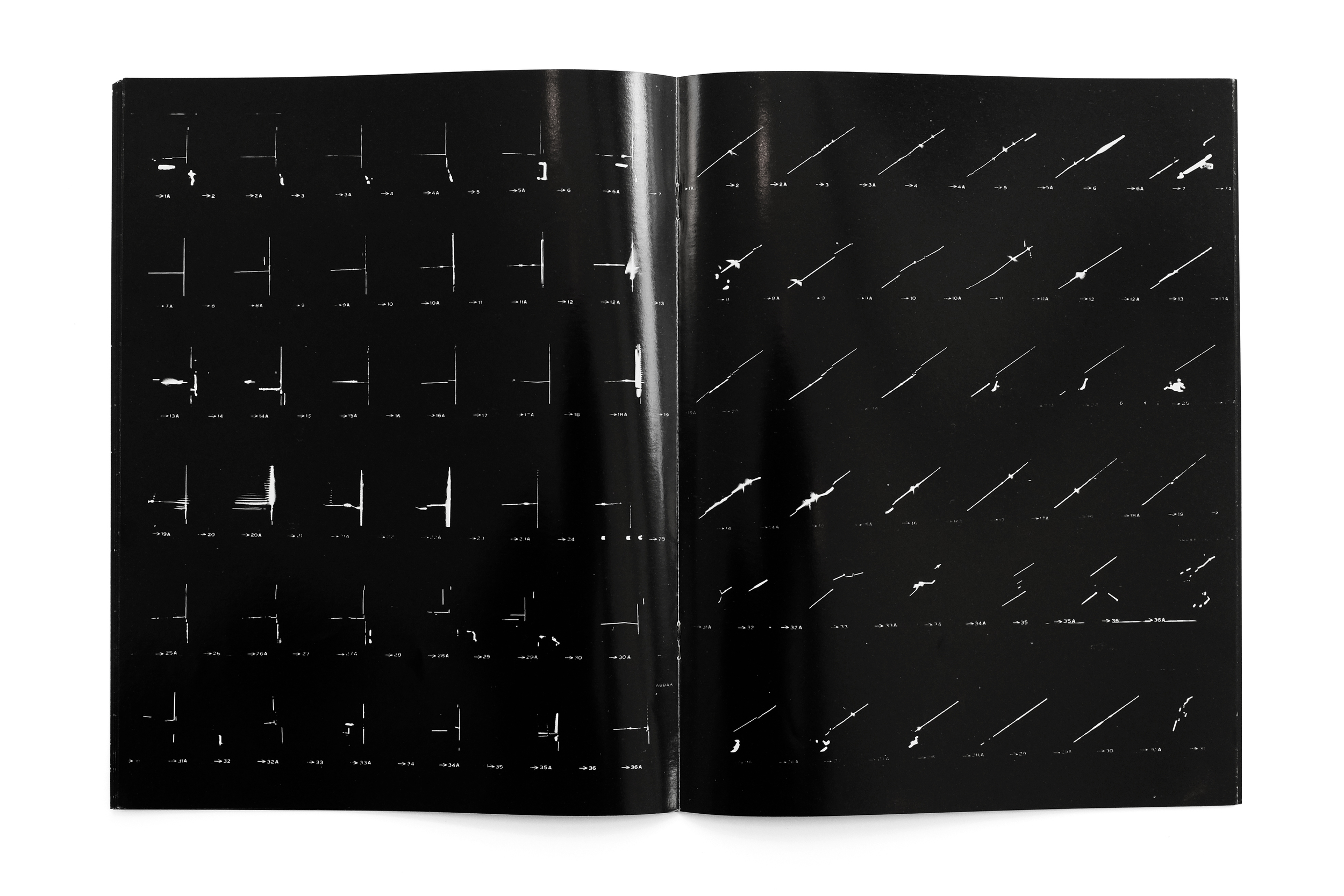

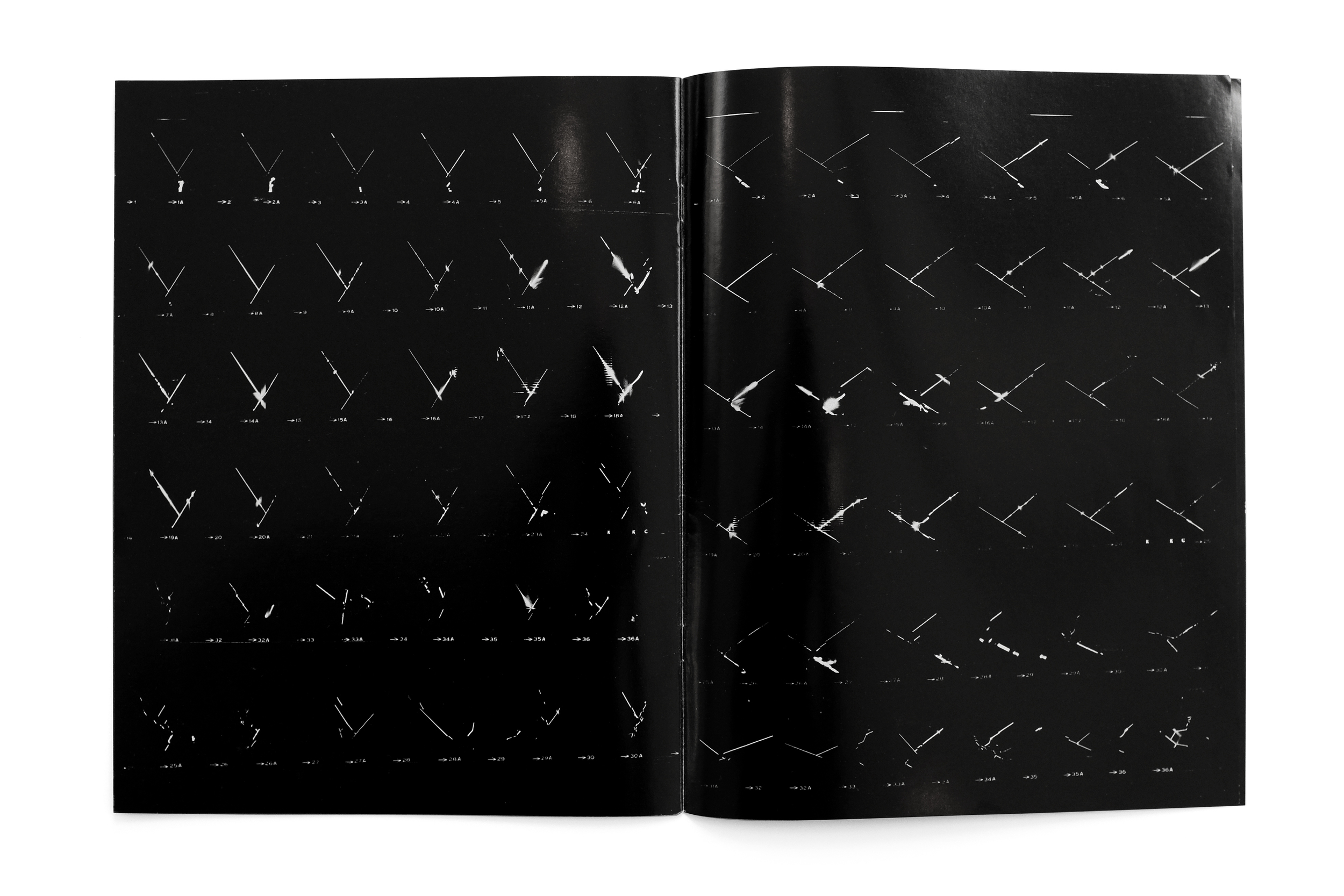

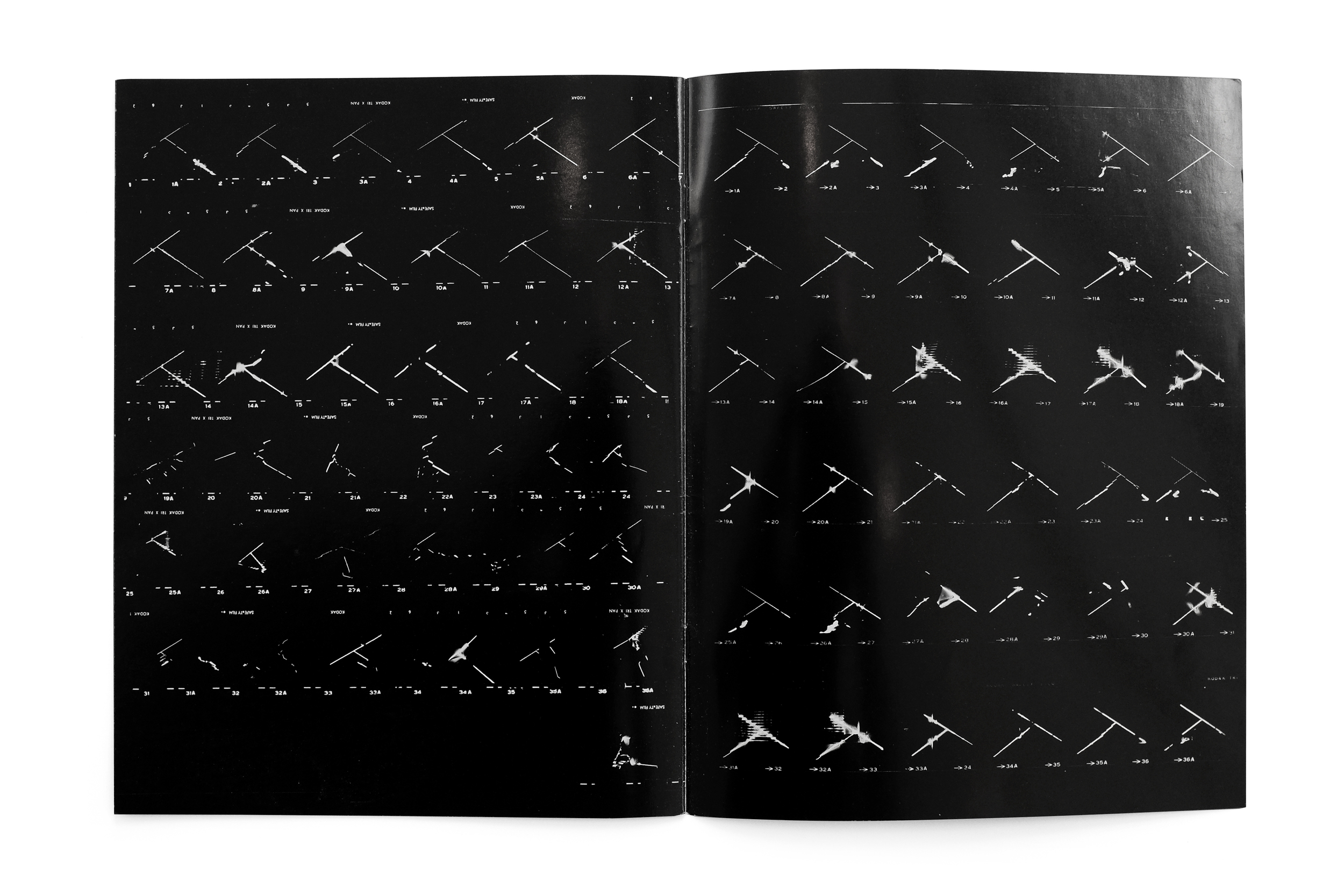

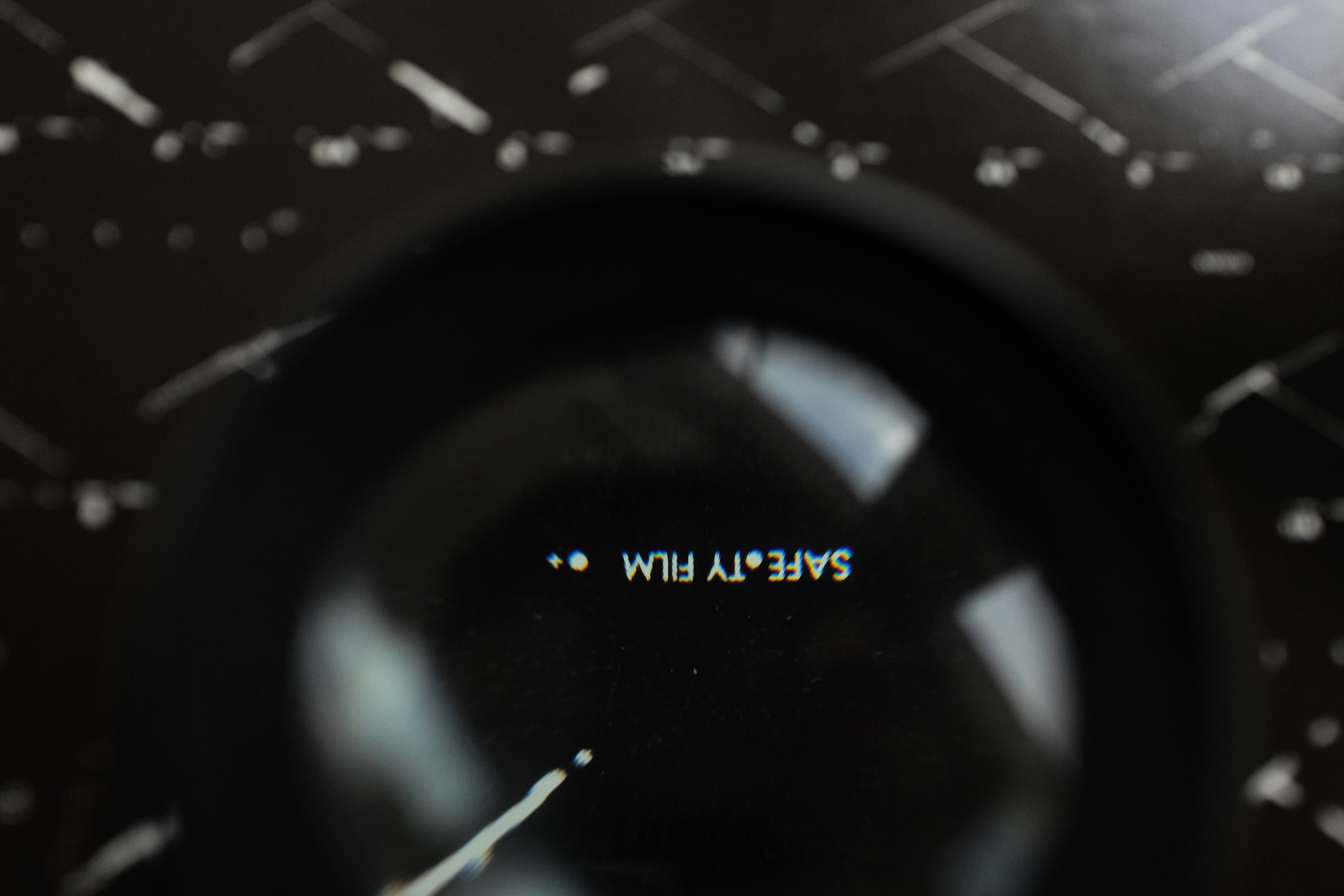

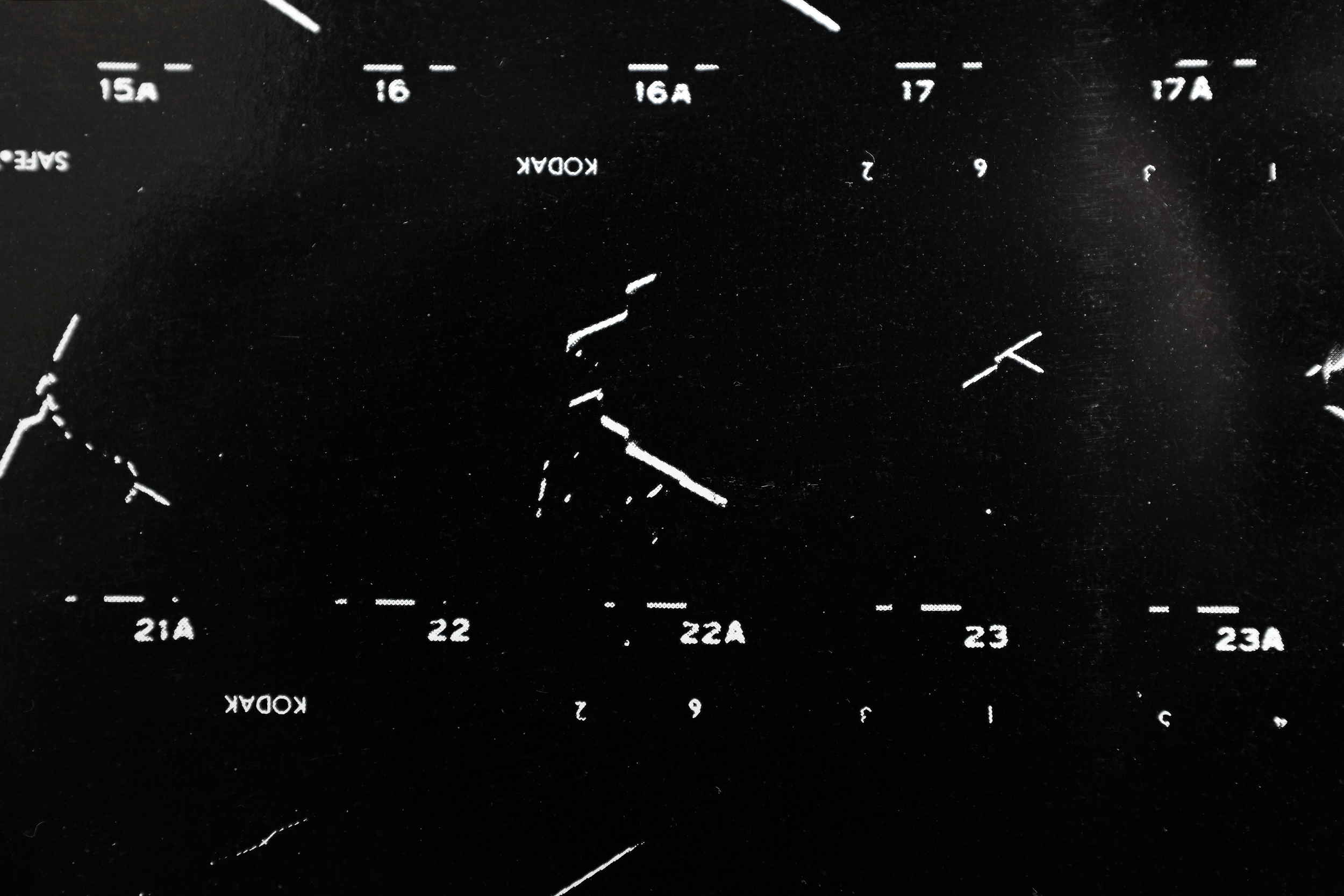

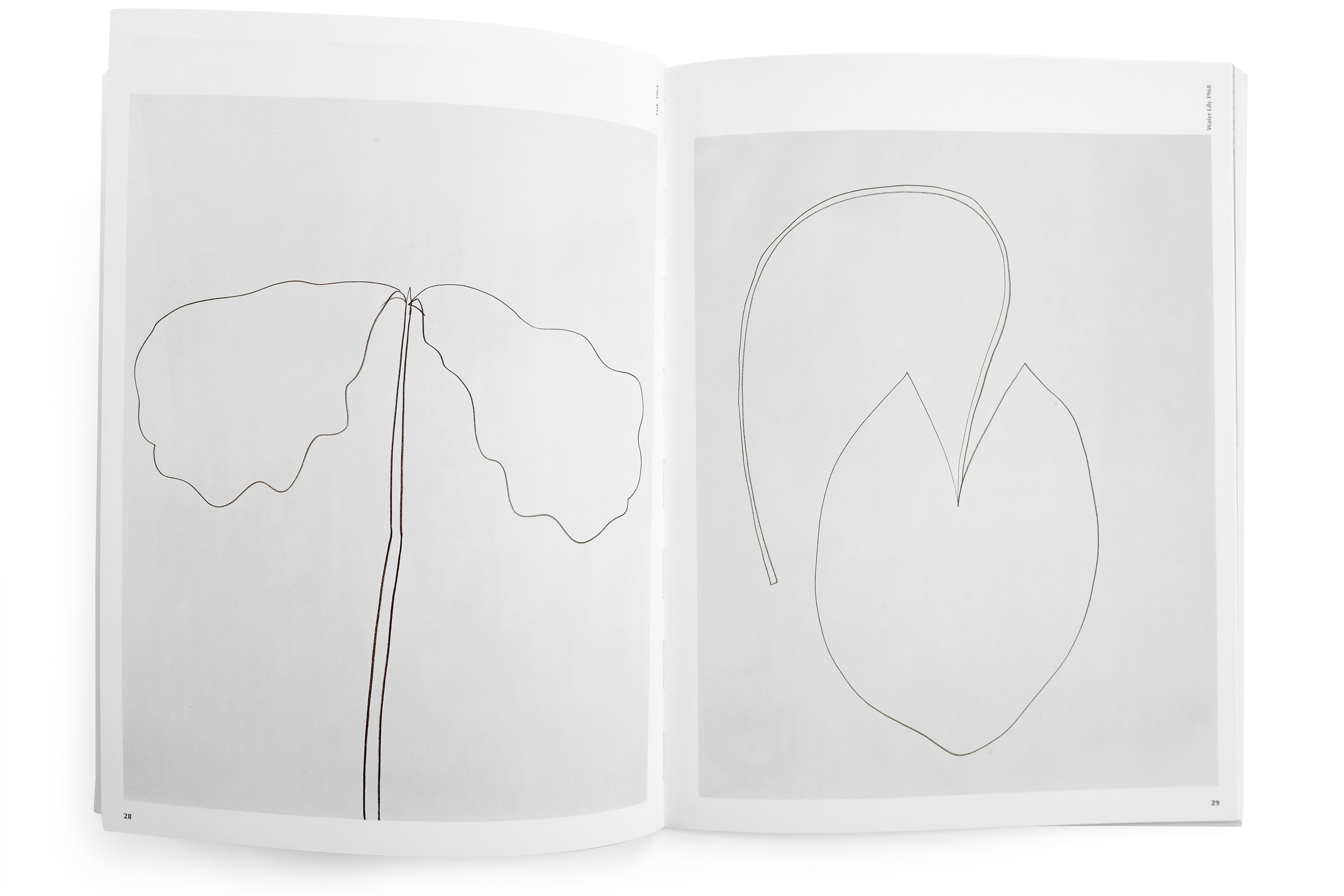

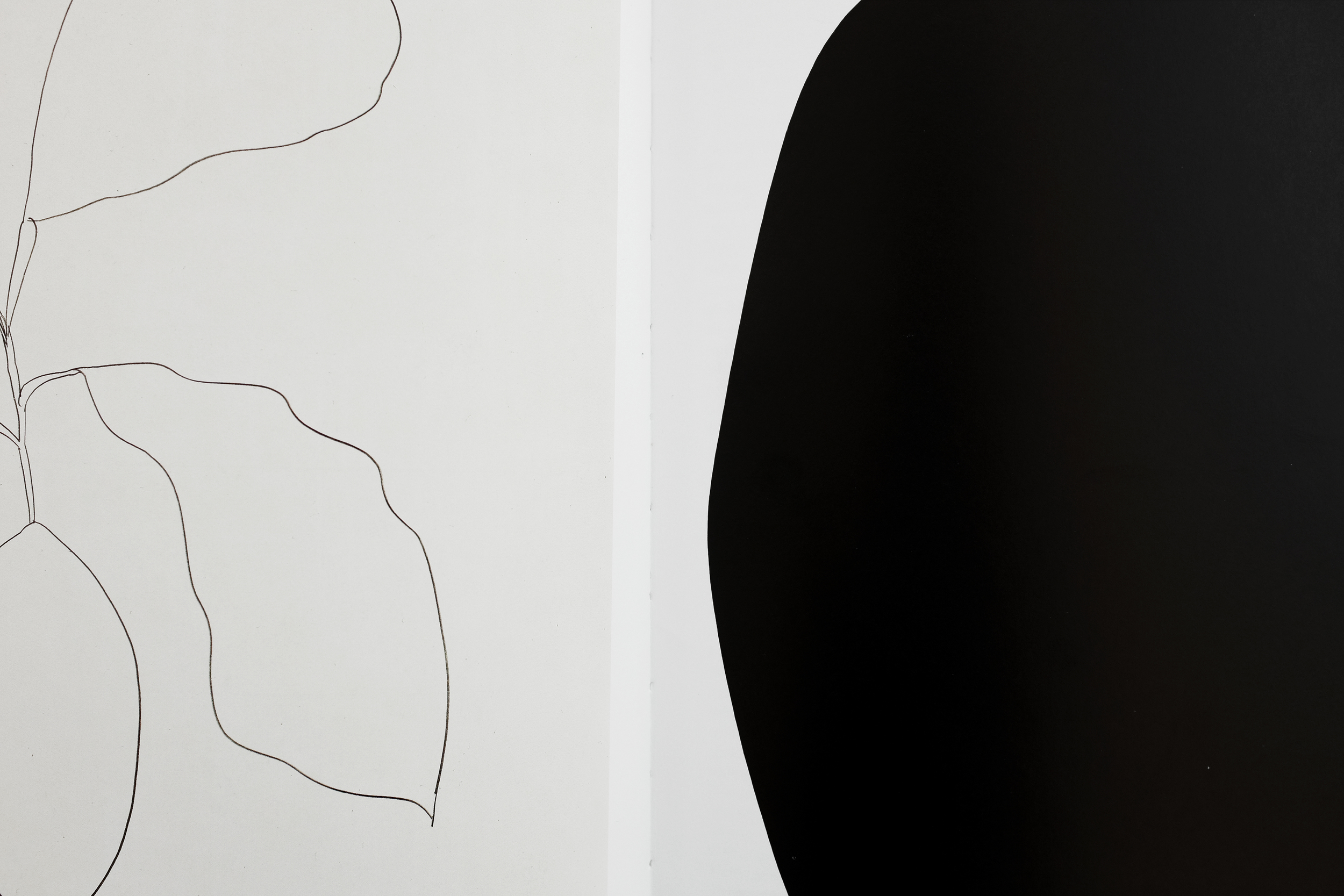

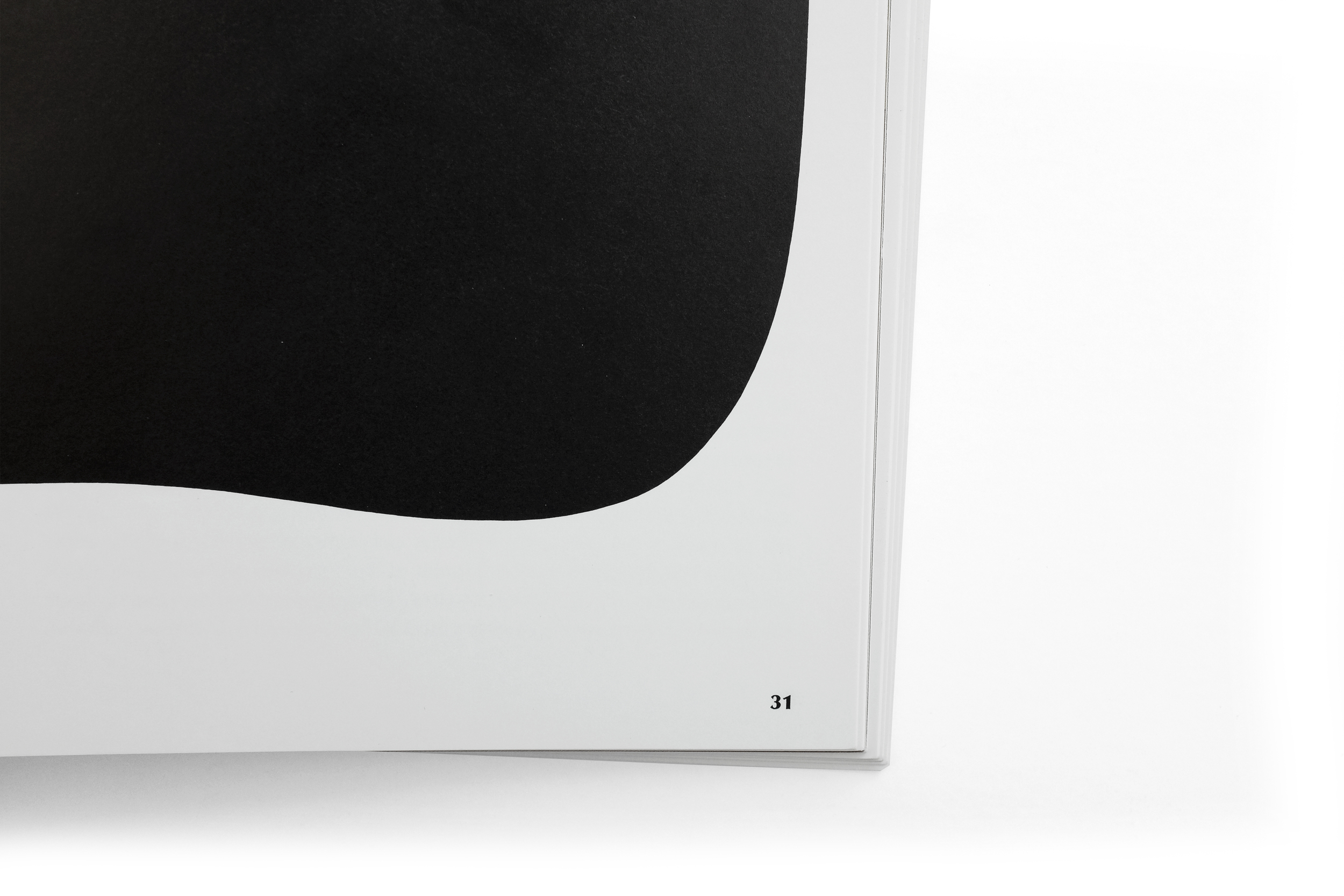

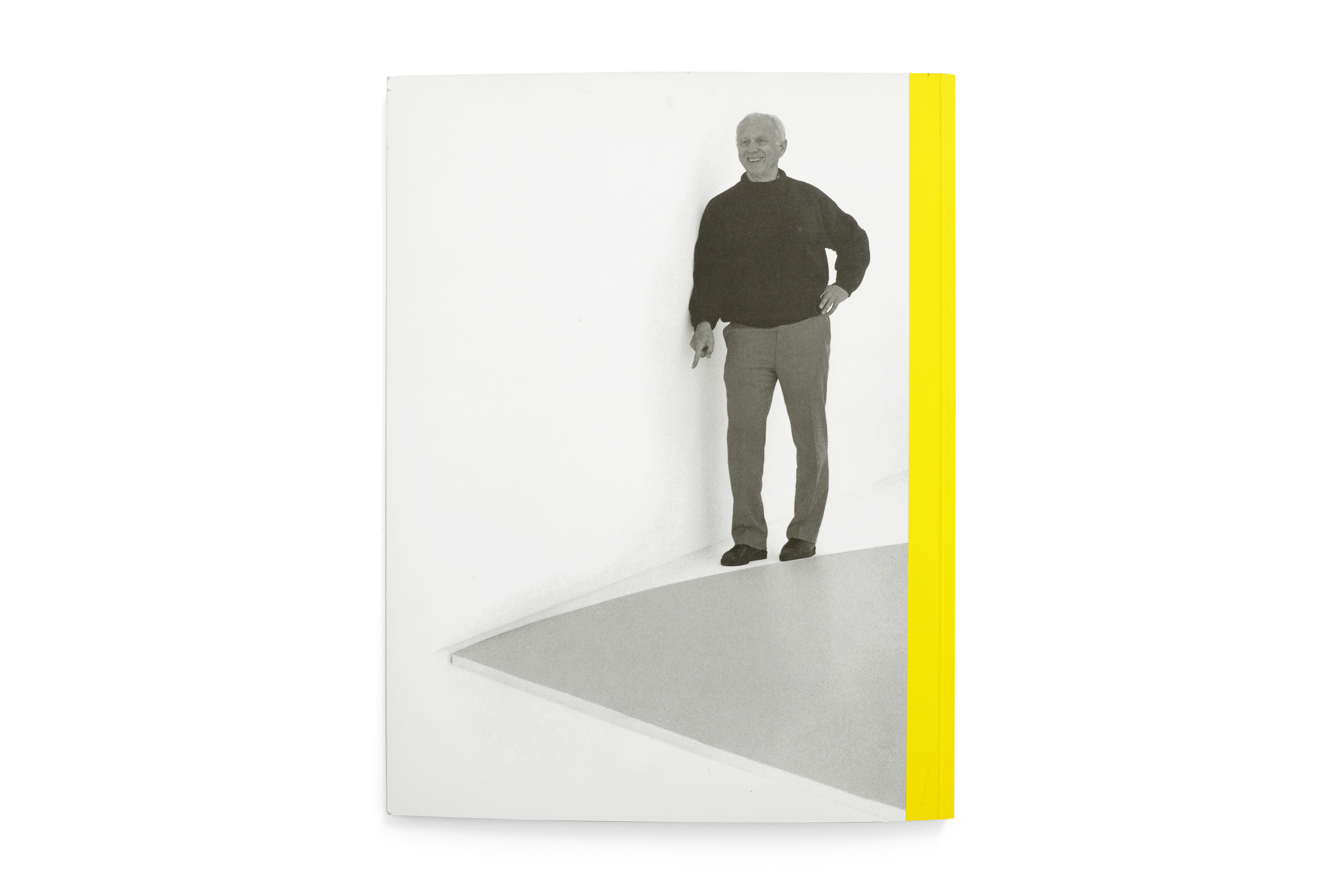

One of my favorite publications from the Stedelijk around this period. The catalog defies interpretation with no supporting text or explanation of the work present within. The black and white catalog is printed on glossy paper, featuring high-contrast photographs of light and shadows against what appear to be window blinds.

W Knoebel Projektion 4/1-11, 5/1-11

1972

Stedelijk Museum

20 pp.

design by Wim Crouwel

The repetition of the individual films strips contrasts the irregularity of their placement on the page, creating a beautiful rhythm throughout. The variation of the forms on the page animate across the book like a stop-motion film.